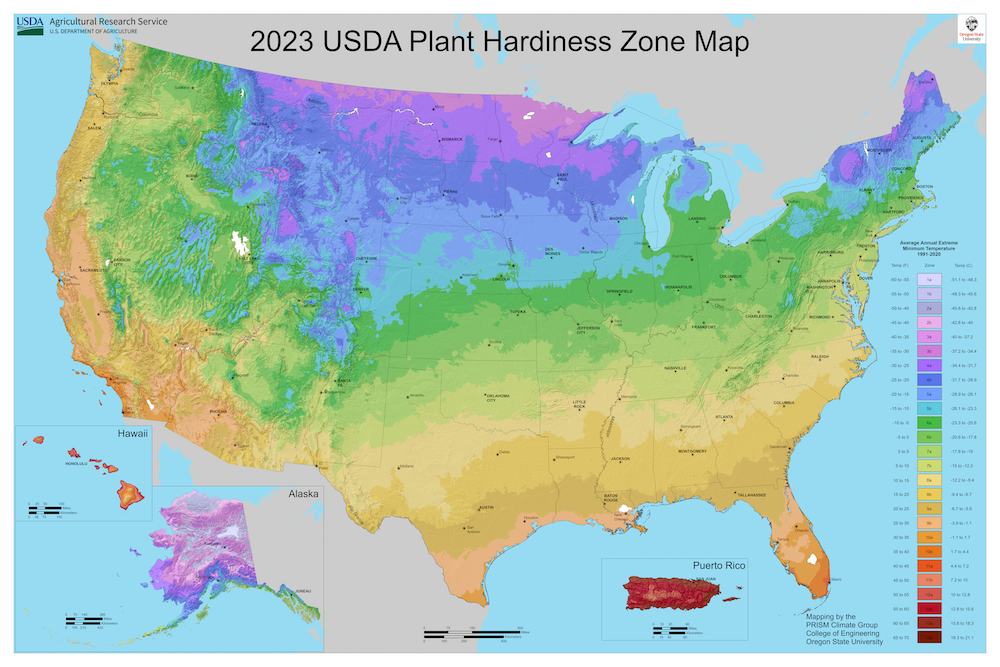

This first version was released in the early 1900s and refined multiple times. In 2012, the map received a massive overhaul backed by a novel climate modeling tool. And last week, the USDA unveiled its newest update, which underscores a warming trend perceived by many growers.

“The 2023 map is about 2.5 degrees warmer than the 2012 map across the contiguous United States,” said Dr. Christopher Daly, a senior professor at the university and the founding director of Oregon State University’s Climate Group, which developed the map with the USDA. “This translated into about half of the country shifting to a warmer five-degree half zone, and half remaining in the same half zone. The central plains and Midwest generally warmed the most, with the southwestern US warming very little.”

Daly helps the USDA generate the widely used plant hardiness map using a system known as the Parameter-elevation Regressions on Independent Slopes Model (PRISM). This knowledge-based system interpolates climate elements in complex landscapes using data such as temperature, precipitation and other climatic factors, generating a continuous grid of weather estimates on a monthly, yearly or event-based basis.

“I’ve been interested in topography, mountains, valleys, rivers, coastlines and how they affect the environment around me,” says Daly. “I took what I knew and learned to do that and developed the first version of PRISM.” Before this model, he found no reliable digital tools that mapped the climate in these complex landscapes. Continuing his research at Oregon State, Daly began to look at rain shadows along the Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountain ranges. His research led to the birth of PRISM.

“That was back in the early nineties,” says Daly. “It’s been improved and updated for the last 30 years and we’re still using it today.”

PRISM remains unique as it combines topographical data with expert knowledge of complex climate extremes and averages. The model is widely used and remains the highest-quality spatial climate data available. As the burning of fossil fuels such as gas and coal warms the planet, developing precise and accurate climate maps and data has become more important to growers and the economy.

One of the major changes in this year’s edition of the hardiness map is the zone boundaries. The USDA states that the new zones are generally about one-quarter-zone warmer than reported in 2012 throughout much of the United States. This is directly related to a more recent averaging period and warming. However, it is also attributed to additional data sources and improved interpolation. PRISM pulled data from 13,412 weather stations, almost 5,000 more than the 2012 data set. One thing that surprised Daly when the map was finalized and compared to the previous version was that it did not change as much as recent climatic warming would suggest. But, he said, “I think in the end we will see warming zones creep northward.”

Across the country, cooperative extensions exist for advice on anything plant-related. These local hubs empower farmers, ranchers and gardeners to meet challenges in growing plants. With a science-based approach, extensions are a great resource for local growers. This includes the volunteer-run master gardener program. Rachel McClure, coordinator of the Master Gardener Program at the University of Nevada, Reno, is just one example of the resources available to communities.

“The USDA plant hardiness zone map gives us an idea of our average high and low temperatures,” says McClure. She comes from a horticultural family and manages about 100 volunteer master gardeners across northern Nevada. “We have contact with thousands of community members every year and recommend this as a source to many people.”

The map is revised every 10 to 12 years by the USDA and reflects data from thousands of weather stations. Being a virtual map, it enables users to examine hardiness zones at a finer scale than before. “This is such a useful tool to home gardeners and everyone alike that it is interactive, and if you go to the web page, you can put in your state and get specific information,” says McClure. The interactivity includes a ZIP code zone finder, allowing users to zero in on their precise location.

“All our home gardeners and users of this map must know that it’s not absolute, it is a general guideline,” says McClure. She adds that Mother Nature is tricky and has a sense of humor, often to the dismay of eager spring gardeners. She echoes Daly in stressing that there are microclimate differences among elevation changes, bodies of water and urban areas. Even across large properties, growers should learn to find cool pockets. As a general tool, though, the map is a wonderful source of knowledge for gardeners and the economy.

“Horticulturalists use the zones also when they’re developing new plants; plant breeders use them a lot to determine which zones they would like to access in terms of markets and they look to our map to see what the cold tolerance would have to be for a plant to be able to survive in that zone,” says Daly. “We want to give gardeners, horticulturalists and others the best information that we can; there’s a lot of economics riding on these maps.” For growers, nurseries, plant breeders and even the USDA Risk Management Agency, the map provides a solid baseline of data and information.

PRISM’s data gets reviewed by a group of horticultural, botanical and climatological experts who then offer feedback and insight to Daly and his research team. From there, he builds the interactive digital map that represents a balance between year-to-year weather fluctuations and the differences between weather and climate, as far as plants are concerned. The same period of data, 1991 to 2020, is the same window that climatologists use to describe normalities in the climate, increasing the robustness of modeling.

“Climate is what you have in your wardrobe, and weather is what you wear today,” explains Daly. This distinction is important when studying the climate and weather. Climate looks at long-term trends to make predictions. PRISM succeeds at this very thing when running weather models. “Because the climate and the plant hardiness statistic is kind of like a weather statistic, it’s that coldest weather that occurred each year where the climate would be a long-term average over many days and years.”

For perennials, these averages are what matters. The finer scale provided by the new map will help growers better understand the data. “Generally speaking, the USDA hardiness zone map gives us a parameter to set,” says McClure. “And if we plan our gardening around those things, more often than not, it will help us be successful.”

article by Richard Bednarski at the Modern Farmer publication

https://modernfarmer.com/2023/11/usda-updated-plant-hardiness-map/?utm_medium=email&_hsmi=286576790&_hsenc=p2ANqtz--sY-E6tx8JGaFn0wfTzkGWSMLhw-FlS_nBfCHA8ern0j24-702imz9gzDvtsnYrf4ZAqFdCrPWRDRRkmV5BVzgRtiP9Q&utm_content=286576790&utm_source=hs_email

RSS Feed

RSS Feed